I expect poems, as a rule, to have some self-contained meaning. I expect each line to build to the next and contribute to a sense of thematic unity in the poem. I know, I know; how 19th century of me. Modernism and postmodernism showed us that poems don’t have to make sense to make us feel something, and I get that. (Hello, Dean Young, John Ashberry, & John Koethe.) But still, some of the old-fashioned traditionalist lingers in me, and I like poetry to feel at least a teeny tiny bit logical.

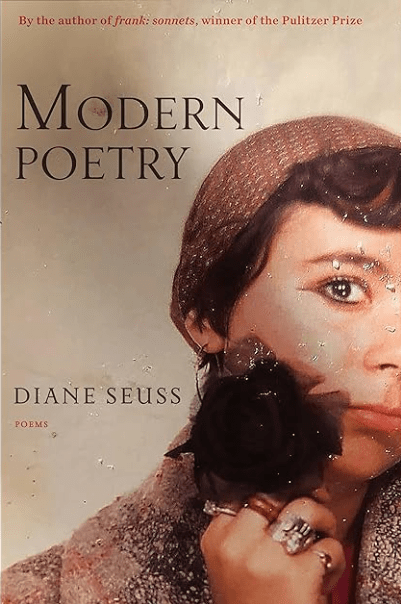

Diane Seuss’s Modern Poetry ain’t that.

I mean, it has moments of self-contained logic. Like in her “Coda,” which starts off with a thesis statement—”The best poem is no poem.” But that’s deceptively straightforward, because of course, what the heck does that mean? And later, “The best poem is without genealogy or fragrance.” Um, okay. But the speaker seems to get that she’s being evasive, deceptively blunt, when she asks “The what? The bill. The unpaid water bill. Out of the spigot / streams a thirsty noncompliance. An antisong.” Poetry as absence. (Nobody better make that the title of an academic paper or I’ll scream.) Rebellion as poetic silence. It’s conceptually interesting, but very vague. But I guess Seuss earns the right to be oblique. She doesn’t owe anyone any explanations. She’s been writing for long enough that she can say what she wants, doesn’t say what she doesn’t want, and leaves. There is a liberation in her decision to be bonkers unclear at times.

This elusiveness is on display in the titular poem of the collection, “Modern Poetry,” in which she pulls a Lana Del Rey, showing her familiarity with kitsch as a way of controlling it (maybe a feminist move?), except instead of the Americana with which Lana Del Rey is obsessed, Seuss is interested in poetry, mentioning, in rapid succession: Roethke (and his toilet); Wallace Stevens; Gerard Manley Hopkins (“Jesuit, maybe bipolar”); “WCW”; Sylvia Plath (“depressed, cheated / on, dead”—gotta love that enjambment); Margaret Atwood; Toni Morrison; Adrienne Rich; Charlotte Perkins Gilman; Plath (again); Sexton; Lorde; Kate Chopin; Alice Walker; Djuna Barnes (a name I had to Google); Langston Hughes. The list grows so long I become disoriented as a reader. The speaker keeps straining to organize the poets and writers. Which are modernist? Then she gets caught up in remembering a woman in the class who “worked at the Kalamazoo airport” and “was shot . . . by her ex-boyfriend.” Then there’s something about a woman named Stephanie (teacher of a woman’s lit class) and she ends the poem with “It was all more than I deserved.” Which does feel like a gesture at unification, but it doesn’t exactly explain all the meandering that came before it. And of course, as any poetry teacher in the land would tell me, it doesn’t have to. This is the point of the collection—rambling assertions of familiarity to the point of sacrilege toward established “modern poets.” Because she can.

Diane Seuss doesn’t care about unity or making sense, except she kind of does, because I believe her when she says that she loves poetry. That doesn’t mean I have to love everything she says about poetry.

“Comma” is a poem I don’t love. “Folk Song” is better.” Seuss has—or at least uses—not a “musical” sensibility, but a sense for drama in a line. She knows how to get the reader’s interest. She is exhibitionist and poet. When she writes about Merry Clayton, background singer in the Tom Verlaine band, “push[ing] out her scream- / song aria three times, and miscarr[ying[ a daughter / the next day. She blamed it on the song / but not her voice.” Then, “When she woke after a car accident . . . she asked only / about her voice”—those lines hit. I have no idea what they mean, but they have this extravagant pathos that makes me put the book down and sigh. Because what haven’t we all given up for beauty and art?

What exactly is this book, Modern Poetry, about? The price of art? The price of life and the redemption of art? I get the sense that the speaker is a functional nihilist—well, a deeply insistent existentialist masquerading as a nihilist, whose poetry becomes God, around which all other things revolve.

That’s not really the approach I take to life. But I get it when Seuss ends the collection with a poem called “Gertrude Stein,” in which the final line, and by extension the final line of the collection, reads: “But the nightingale, I said.” I get it because I’ve come back to the same place many times. At some point, we all end up clinging to the bathroom counter, trying to find ourselves in our reflections again, unsure what exactly to trust except for certain old songs, certain old beliefs, the habit of making art that turns us human even when it would be easier not to be. And that we can’t give up on, because certain habits, including the habit of liking poetry, are tenacious. And that I will grant this collection—it’s tenacious. Nonsensical. But tenacious nonsense, and I think I like that. It’s not for everyone, but maybe give it a shot. You might find you have more in common with Seuss than you think.